Know Your Data: Fishing Gear

This is part of our series to help seafood professionals, newcomers and enthusiasts navigate the complexities of sourcing data. For more, read about species, vessel identifiers and harvest areas.

For as long as humans have lived near water we have been fishers, and for as long as we have been fishers we have been refining the tools of our trade—hand, hook and net. The modern diversity of fishing gear reflects not only generations of creative and hardworking people but also the wide range of environments where we fish and the behaviors of our delectable prey.

The sourcing data we have covered in this series so far are relative newcomers: scientific names showed up in the 1700s, exclusive economic zones in the 1970s and sorting out the best way to identify fishing vessels is still a work in progress. Fishing gear, by contrast, was around long before written language existed to record it. I believe the extraordinary time series and diversity of uses explain the fact that of all the types of data Goldfish has streamlined, fishing gear has been the most challenging by far. It has literally taken years to transform the world's fishing gear types into a useful database, but it was necessary to build software that makes 1) commerce more efficient, 2) regulations more effective and 3) market access more fair. Here are a few insights from that process.

Categorization of Gear

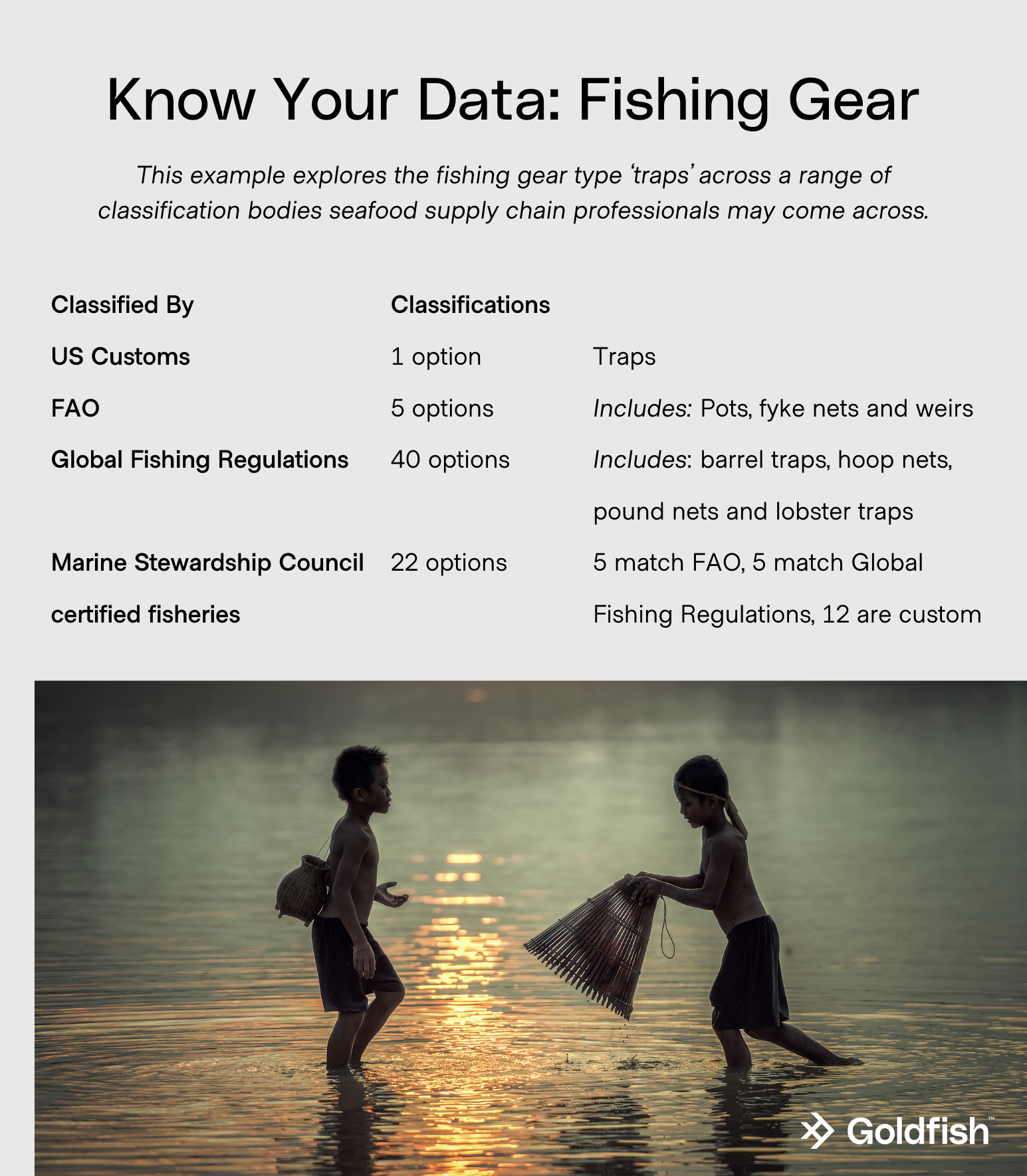

One of the major challenges of classifying fishing gear is determining whose opinion truly matters. For seafood commerce, we have narrowed it down to these three:

FAO

In 1980 the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) published a standardized list of gear types that is still widely used today to classify fishing activities for various purposes. Thematically this is similar to FAO's role in mapping the world's Major Fishing Areas, and the downsides of relying on FAO's gear list are also similar:

- They have to be aligned with national fisheries regulations to have value in compliance screening;

- the list is far from comprehensive—FAO's own website includes a number of gear types that fall outside its own standard; and

- it does not cover aquaculture.

Government Agencies

As an assurance provider, we focus heavily on what regulators are looking for. There are two types of government agencies that matter most to seafood commerce: fisheries management and trade. Fisheries management agencies determine what gear can be used where, when and by whom through regulations. We found over 450 distinct gear types specified in commercial fishing regulations around the world, many of which are similar to FAO gear types but with additional specifications such as the depth at which the fishing gear must be deployed.

Then we come to trade. For US imports, Customs and Border Protection offers less than two dozen gear options to cover all seafood imports. This means that much of the nuance in fisheries regulations has to be reclassified under more generic terms—in many cases the best option is simply 'other'—to clear customs. This can make due diligence particularly challenging for importers as well as trade monitoring agencies like NOAA that are expected to use this generalized data to screen imports for illegal fishing risk.

Ecolabels and Certifications

Consider all of the gear types we just discussed, and now let's invite NGOs to the party. There are a multitude of seafood certifications, ecolabels, standards and materials that advise retailers and consumers with varying levels of gear-specific details. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is the world's largest seafood ecolabeling program and one of our customers, so we have been particularly interested in exploring how Goldfish can help buyers ensure they are purchasing seafood from MSC certified fisheries. We found that while the MSC usually uses FAO gear types, they will sometimes make modifications that deviate from the FAO standard, fishery management regulations, or both.

Here is an example of how we worked to reconcile fishing gear types across organizations, so someone trying to classify a 'pound net' for customs clearance doesn't have to guess if it might be a type of gill net (nope), drift net (still no), trap (yes!) or something else entirely.

Our Advice

For companies: If you can track the gear type as listed on the fishing permit that will be your best shot at retaining the level of granularity a regulator or buyer might ask for down the line. At a minimum, use the best fit FAO gear code for wild caught seafood. Either of these can be aligned with US customs classifications (and Goldfish does this automatically for broker reports).

For Government: US Customs and Border Protection could improve the utility of gear type information through a number of possible adjustments, such as replacing the current options with open text, aligning them with FAO and other common gear types, or augmenting the existing list with a few sourcing options that are highly regulated.

The deep research and work that went into creating an unassuming 'gear type' drop down menu showcases what we value most: solving problems without creating new ones. That can mean spending lots of time on improvements that aren't readily visible to users but make a huge difference in the long run. To learn more about how Goldfish can help you get what you need from sourcing data, contact us or visit www.goldfish.io.